Gender Roles in Hit Country & R&B/Hip-Hop Lyrics (1990-2021): A TidyText Analysis With R

In this post, we will return to the dataset containing song lyrics from country and R&B/hip-hop songs that we analyzed in the previous post. The data consist of popular songs from the Billboard year-end music charts, and we will use the tidy analytic approach to text analysis to analyze how the two genres differ in their descriptions of men and women. This analytical approach is taken fairly directly from Julia Silge’s analyses of gendered language in Jane Austen novels and movie scripts.

You can find the data and code used for this analysis on Github here.

The Data

The data come from two different sources. The sampling frame is the Billboard year end top 100 song charts for two different genres: country and R&B/hip-hop from the years 1990 until 2021. Note that while the second genre encompasses both R&B and hip-hop, from the period 1990 onward, the bulk of the songs listed lean more towards hip-hop than R&B.

I scraped most of the Billboard data in July 2021 and used the excellent Python package LyricsGenius to extract the song lyric data from the Genius website. Hat tip to Mark MacArdle’s script on Github that made it really straightforward to get these data!1

In total, the raw dataset contains lyrics for 2754 R&B/Hip-Hop songs and 2444 Country songs that appeared in the Top 100 year-end Billboard song rankings. Some songs are repeated in the raw dataset, because a given song can be popular across multiple years. After removing duplicate songs, we are left with 4620 songs for the current analysis: 2423 R&B/hip-hop and 2197 country songs.

The head of our dataset, called clean_data, looks like this:

| song | artist | genre | lyrics_clean | lyrics_scrubbed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nobody's Home | Clint Black | Country | Move slowly to my dresser drawers Put my... | slowly dresser drawers blue jeans cowboy... |

| Hard Rock Bottom Of Your Heart | Randy Travis | Country | Since the day I was led to temptation An... | day led temptation weakness love prayed... |

| On Second Thought | Eddie Rabbitt | Country | Sometimes a man does things without half... | man things half thinking understand call... |

| Love Without End, Amen | George Strait | Country | I got sent home from school one day with... | school day shiner eye fighting rules mat... |

| Walkin' Away | Clint Black | Country | Walkin' away I saw a side of you That I... | walkin knew someday goodbye wrong start... |

| I've Cried My Last Tear For You | Ricky Van Shelton | Country | When you left me lonely here I thought t... | left lonely thought drown tears wiped pl... |

The column lyrics_clean contains the song lyrics, from which I’ve removed carriage returns and additional text that is not part of the lyrics (e.g. [Verse 1], etc.). The column lyrics_scrubbed contains the same text as lyrics_clean, but with stopwords removed and all letters set to lower case.

The Tidy Approach to Text Analysis

We have already used the tidy approach to text analysis in a previous post examining the text of Pitchfork music reviews. The basic idea behind the tidytext framework is that we represent our data with 1 line per token (a sub-division of a longer text, typically a single word although here we will use two-word combinations called bigrams), keeping track of important meta-data (e.g. the song title, genre, etc.) in additional columns.

Step 1: Lyrics Texts to Bigrams

In the first step, we will pass our individual song lyrics column in the original data and extract two word combinations called “bigrams”. We will also do two counting exercises in order to select which bigrams to include in our analysis.

The first exercise will be to count how many times each bigram appears in each song. The second will be to count how many times each bigram appears in each genre. The reason that we do this is to identify which bigrams only appear in a single song. Because song lyrics can be more repetitive than other types of written text, we want to exclude bigrams that appear very frequently but only in one song.2

We can accomplish all of this with the dplyr and tidytext packages, and view the head of the resulting dataframe, with the following code:

# load packages that we'll need

library(readr)

library(dplyr)

library(tidytext)

library(tidyverse)

library(stringr)

# make a tidy df with the bigrams

song_bigrams <- clean_data %>% select(song, genre, lyrics_clean) %>%

# extract bigrams (2-word combinations) from the "lyrics_clean" text column

unnest_tokens(bigram, lyrics_clean, token = "ngrams", n = 2) %>%

# count - how many times does each bigram appear in each song?

group_by(song, bigram) %>%

mutate(n_bigram_per_song = n()) %>%

ungroup() %>%

# count - how many times does each bigram appear in each genre?

group_by(genre, bigram) %>%

mutate(n_bigram_per_genre = n())

head(song_bigrams)Which returns a dataframe called song_bigrams, with 1,924,106 rows, one for each two-word combination in all of the songs in our corpus. The head of the song_bigrams dataframe looks like this:

| song | genre | bigram | n_bigram_per_song | n_bigram_per_genre |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nobody's Home | Country | move slowly | 1 | 1 |

| Nobody's Home | Country | slowly to | 1 | 2 |

| Nobody's Home | Country | to my | 1 | 200 |

| Nobody's Home | Country | my dresser | 1 | 2 |

| Nobody's Home | Country | dresser drawers | 1 | 1 |

| Nobody's Home | Country | drawers put | 1 | 1 |

We can see from the column n_bigram_per_song how many times each line’s bigram appears in the song, and in the column n_bigram_per_genre, how many times each line’s bigram appears in the song’s genre. When these two columns are equal, it means that the given bigram on a given line appears in a single song in its genre. In the sample of the data shown above, “move slowly” appears once in the song “Nobody’s Home”, and once in the country music genre: meaning that this bigram only appears in a single song. In the analysis that follows, we will exclude rows where this is the case, in order not to consider bigrams that appear frequently, but only in one song.

Step 2: Counting Gender Bigrams Per Genre

Next, we take our song_bigrams dataframe and produce an aggregated dataframe with the counts of each bigram in each genre. Specifically, the following code first removes bigrams that only appear in a single song (e.g. lines where n_bigram_per_song is not equal to n_bigram_per_genre), and aggregates the bigrams to produce a dataset which contains one line per bigram per genre, with the counts of the number of occurrences of each bigram in a column called “total”. Note that we also split the bigrams into two columns, one per word, and only retain those bigrams that begin with she or he.

Our code to produce this aggregated dataset looks like this:

bigram_counts <- song_bigrams %>%

# we *only* want bigrams that appear in more than 1 song

# we can make this selection by only keeping rows

# where n_bigram_per_song is not equal to n_bigram_per_genre

# (if these are equal, it means that the bigram only appears in 1 song

# in the given genre)

filter(n_bigram_per_song != n_bigram_per_genre) %>%

# count the number of occurrences of each bigram in each genre

count(genre, bigram, sort = TRUE) %>%

# split up the bigrams into two columns, one per word

separate(bigram, c("word1", "word2"), sep = " ") %>%

# only keep bigrams that start with he or she

filter(word1 %in% c("he", "she")) %>%

# removes some repetition - she she

filter(word1 != word2) %>%

# rename the bigram count column "total"

rename(total = n)

head(bigram_counts)And yields the following dataset, called bigram_counts, with 880 rows:

| genre | word1 | word2 | total |

|---|---|---|---|

| R&B/Hip-Hop | she | got | 396 |

| R&B/Hip-Hop | she | said | 285 |

| Country | she | was | 268 |

| Country | she | said | 182 |

| R&B/Hip-Hop | she | like | 178 |

| Country | he | said | 176 |

Step 3: Visualize Common Words Paired with “She” and “He”

The first set of analyses will examine the common words paired with “she” and “he”, separately for each genre. We can take our bigram_counts dataframe, and for each genre, plot the top 10 most frequent words that are paired with “she” and “he” (a huge hat tip to Julia Silge’s post on ordering bar charts per group). The colors used for the gendered descriptions are taken from this very interesting blog post on using color to represent topics related to gender and male/female differences.

The code to produce the country chart is as follows (the R&B/hip-hop code is available in the Github repo):

# colors inspired by:

# https://blog.datawrapper.de/gendercolor/

# #8624f5 - for women

# #1fc3aa - for men

hex_pal = c('#8624f5' , '#1fc3aa')

# country

# https://juliasilge.com/blog/reorder-within/

bigram_counts %>%

# select only country songs

filter(genre == 'Country') %>%

# group by first word of bigram

group_by(word1) %>%

# and keep only the 10 most-frequently

# occurring bigrams

slice_max(total, n = 10) %>%

ungroup %>%

# set factor levels so that graph for women appears

# on the left

# and re-order the dataset - by second bigram word,

# then the total number of occurrences and first bigram word (she/he)

mutate(word1 = factor(word1, levels = c('she', 'he')),

word2 = reorder_within(word2, total, word1)) %>%

# set up our plot with ggplot

ggplot(aes(word2, total, fill = word1)) +

# we want a bar chart with no legend

geom_col(show.legend = FALSE) +

# separate panels for she & he, panels

# can have their own scales

# (there are more words for women than men)

facet_wrap(~word1, scales = "free_y") +

# set the labels for the chart

labs(x = NULL,

y = "Number of occurences following 'she' vs. 'he'",

title = "Most common words paired with 'she' and 'he' in popular country songs",

subtitle = "Billboard Top 100 Year End Country Songs (1990-2021)",

caption = "(N = 2,197)") +

# flip x and y in chart

coord_flip() +

# black and white theme (more basic than standard one)

theme_bw() +

# set the colors

scale_fill_manual(values = hex_pal) +

# from tidytext - Reorder a column before plotting with faceting,

# such that the values are ordered within each facet.

# (re-order words separately for she/he facet panels)

scale_x_reordered() +

# set limits for axis showing the total number of occurrences

scale_y_continuous(expand = c(0,5))Common Words Paired with Gender Pronouns in Country Music

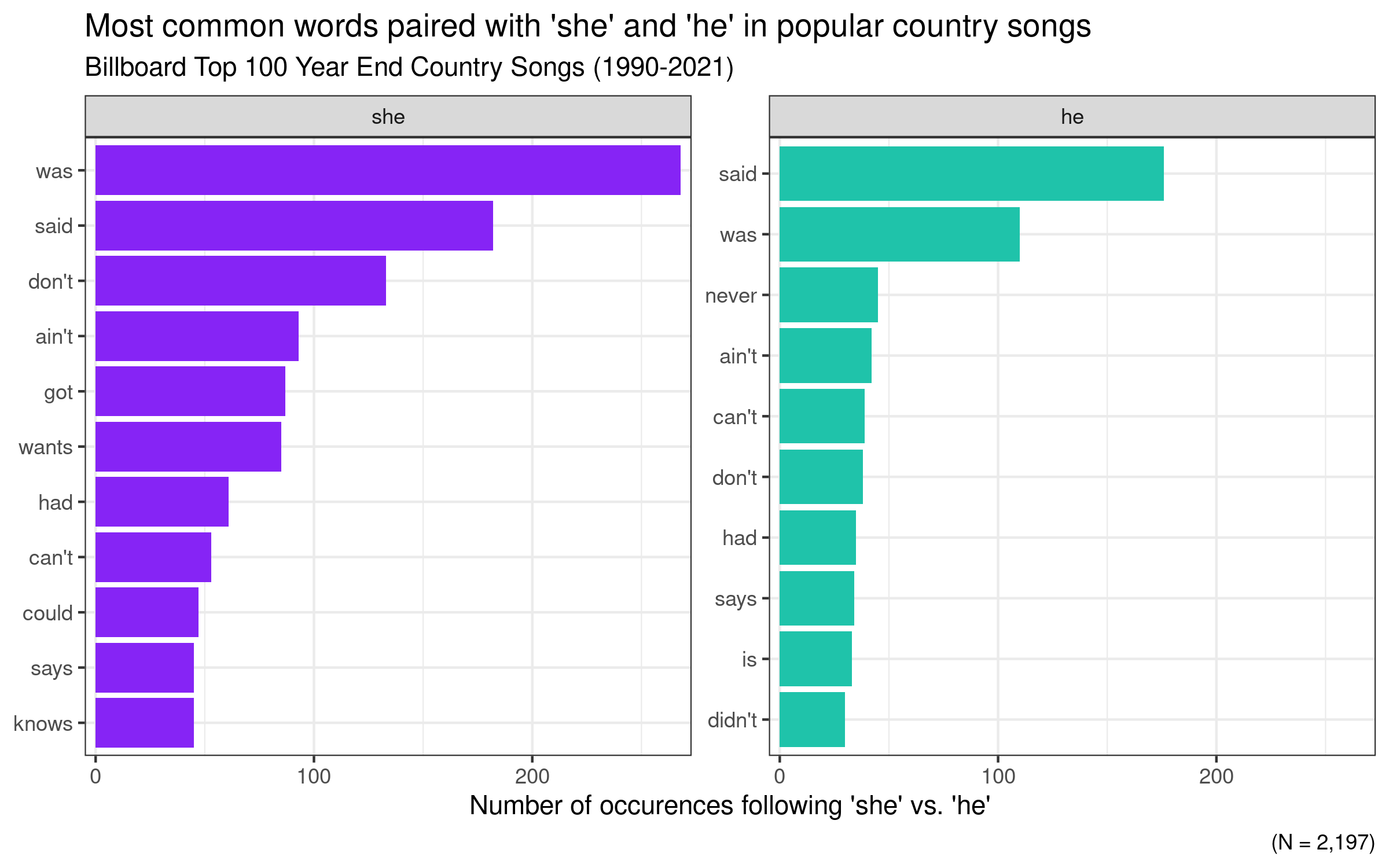

The plot for country music looks like this:

The first observation is that there are far more bigrams that begin with “she” than begin with “he.” This is perhaps unsurprising - most of the country songs in the Billboard lists are sung by men, and a common theme (as we saw in the previous post) is love and romantic relationships, which in this traditional music genre, tend to be with women.

The second is that the most frequent words across genders are more-or-less the same. In country music, gender pronouns are followed by the following words: said, was, don’t, ain’t, can’t, says, and had. All in all, country music lyrics concern themselves with what women and men are saying (said, says), and what they were doing (was, had), and what they are not (don’t, ain’t, can’t).

Common Words Paired with Gender Pronouns in R&B/Hip-Hop Music

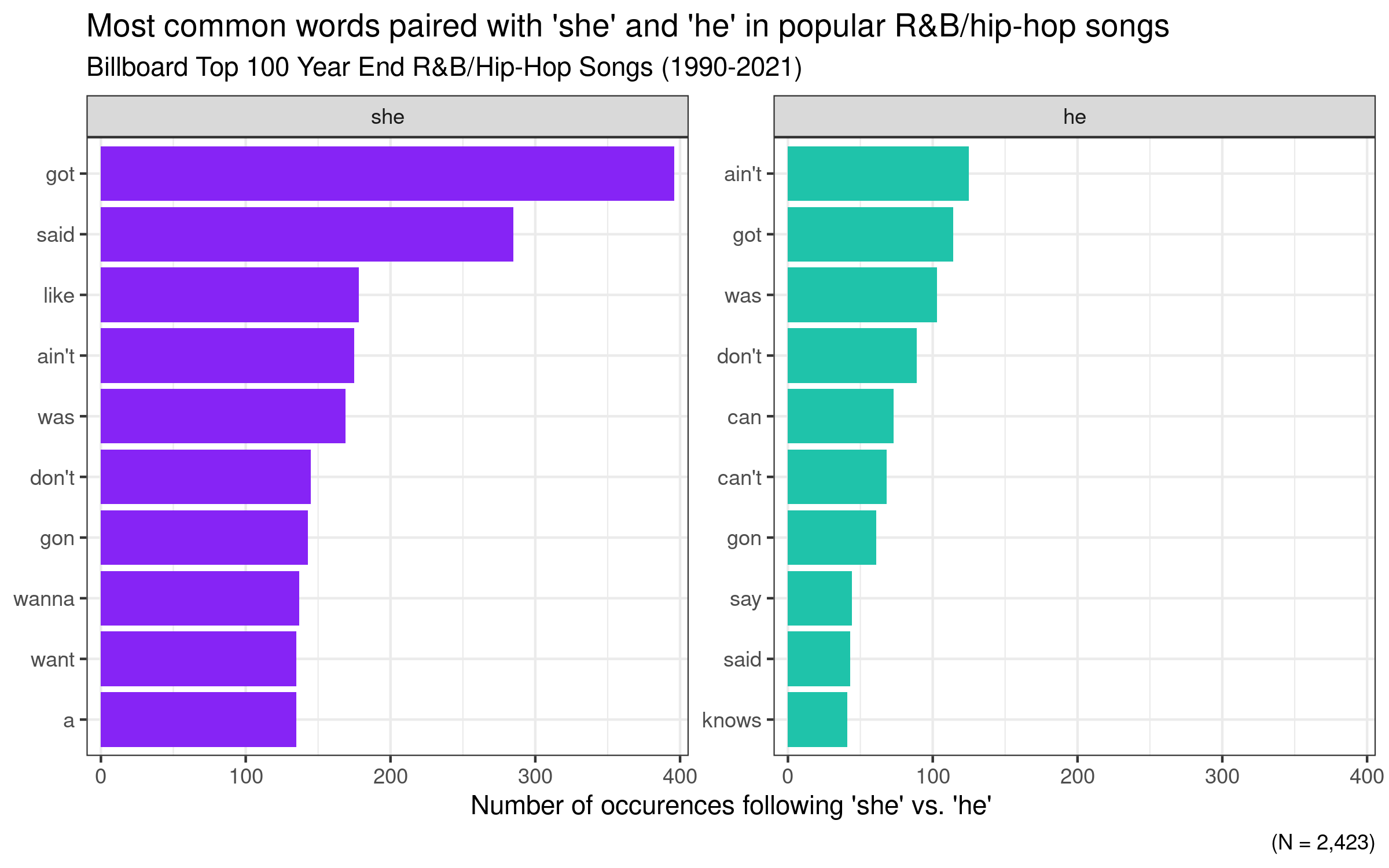

The plot for R&B/hip-hop music looks like this:

As with country music, there are far more bigrams that begin with “she” than begin with “he”. As with country music, the R&B/hip-hop charts tend to be dominated by male performers, with the narrative focusing on women.

There is also a great deal of overlap among the words following she and he in R&B/hip-hop music (though less so than for country), with the following words common among both genders: got, said, ain’t, was, don’t, and gon. As with country music, in R&B/hip-hop lyrics, the lyrics describe what men and women are saying, doing and what they are not.

Step 4: Visualize Differences Between Words Paired with “She” and “He”

The final analyses will focus on the differences in the bigrams that start with she and he. In other words, how do country and R&B/hip-hop music genres describe women differently from men? This analysis is focused on gender differences within each genre, though we will also comment on differences between the genres.

In order to conduct this analysis, we need to analyze the bigrams in terms of their differences across the genders, which we will do separately per music genre. We use code adapted from here and here to do so. The following code describes the process for country music; for the analagous analysis for Hip-Hop/R&B music, check out the Github repo.

We first filter out any bigrams that appear fewer than 10 times in the country song lyrics. We then create separate columns for each bigram with the counts following “she” and “he”, and then calculate a ratio which is the number of times the bigram appears following each gender pronoun, divided by the total number of bigram occurrences for each gender pronoun. Finally, we take the binary logarithm (log2) of the ratio of the bigram ratios for “she” vs. “he” - this is our “log odds ratio” which we will use as the x-axis in our visualization. The advantage of using the binary logarithm (e.g. log2) instead of the natural logarithm (e.g. log) is that an increase of 1 on the log2 scale corresponds to a doubling of the values on the original scale, making for an intuitive scaling in the x-axis of our graph.

The following code performs these operations and makes the plots, using the colors we defined above for women and men:

# country

word_ratios_country <- bigram_counts %>%

# select only country music songs

filter(genre == 'Country') %>%

# group by music genre and second bigram word

group_by(genre, word2) %>%

# filter any bigrams that appear fewer than 10 times

filter(sum(total) > 10) %>%

ungroup() %>%

# long to wide transformation, making separate columns

# for she and he, with the total number of occurrences per gender

# as data points. Fill empty cells with zero

spread(word1, total, fill = 0) %>%

# https://www.tidytextmining.com/twitter.html#comparing-word-usage

# ratio, for each bigram: total uses of bigram (+1),

# divided by the sum of all of the bigram uses (+1)

mutate_if(is.numeric, list(~(. + 1) / (sum(.) + 1))) %>%

# divide she ratio by he ratio, and take the log2 of the result

# we use log2 because the interpretability / logic is better

# with log2 vs. log (increase of 1 indicates doubling of original metric)

mutate(logratio = log2(she / he)) %>%

# sort the dataframe by the log ratio variable

arrange(desc(logratio)) Differences Between How Women and Men Are Described in Country Music

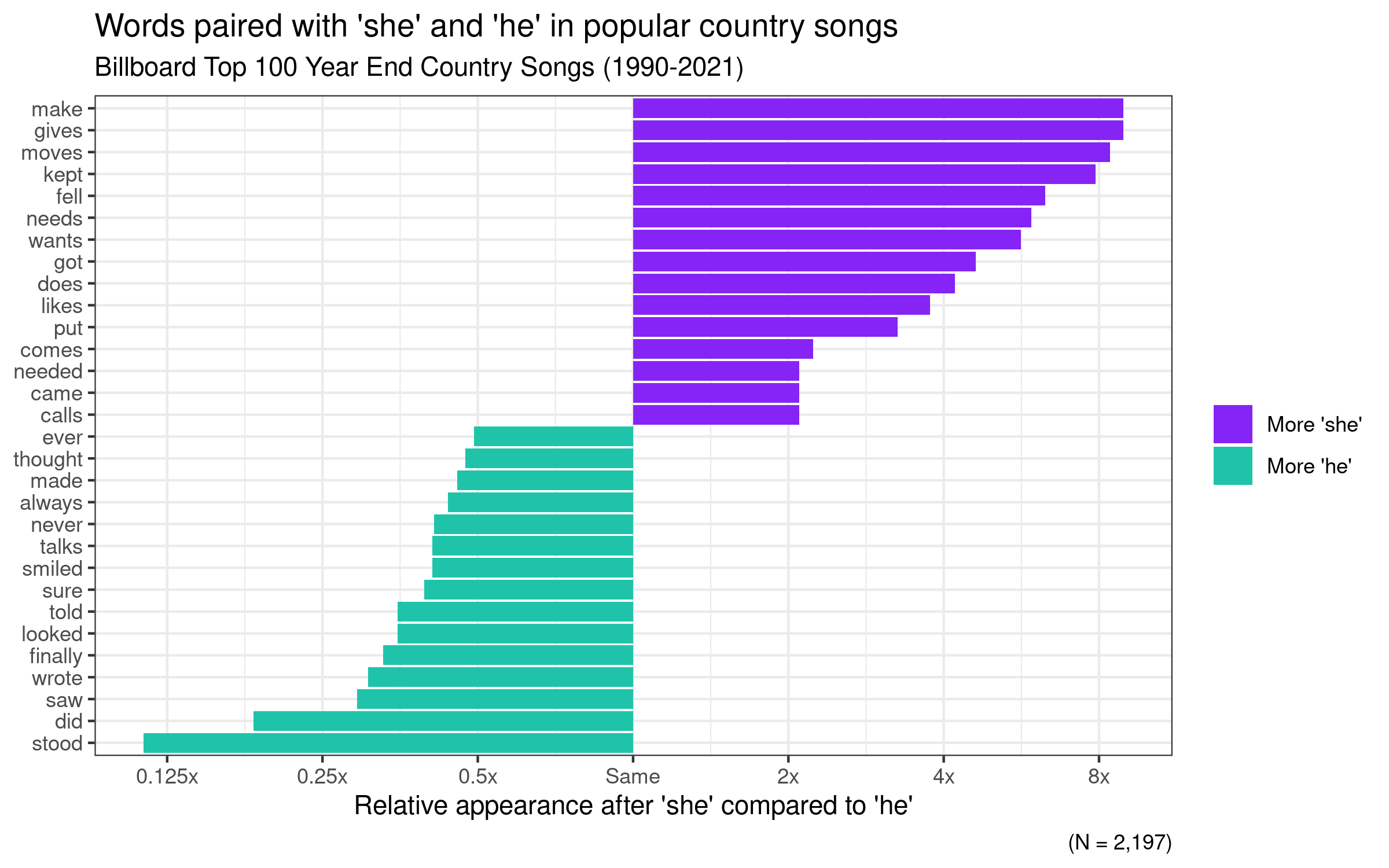

The plot for country music looks like this:

There are clearly differences between how women and men are described in country music. Here are some of the things that jump out to me in the above plot.

Women

-

There is a group of words that describe women in terms of desires, needs and pleasures (needs, needed, wants, likes). Women, more so than men, are described in terms of their preferences - not by what they do, but by what they need, want, or enjoy. Examples include - she needs him, what she wants is love, and she likes to feel the sand beneath her feet.

-

Giving is an important theme for women in country music. Women are described as giving many different things (She gives me hot and cold fever, she gives me a kiss, she gives you the green light, she gives her love, she gives me hope); the receivers are typically men. By describing them as givers, the country lyrics attribute some agency to women, although one could argue that someone who gives something to someone else is in a comparatively subservient position to the recipient.

-

Falling (fell) is another important word that occurs more frequently following “she” than “he.” In country music, this refers (perhaps unsurprisingly) to falling in love (she fell this time and broke her heart in two, she fell in love). As we saw in the previous post, in both country and R&B/hip-hop, love and romance is a prominent theme. In the country music lyrics, it’s more often the women who fall in love (with men, exclusively, in these popular songs).

-

There are two variations on coming (comes & came) that are more common following “she” vs. “he” in country lyrics. Upon closer examination of the lyrics, it appears that these word choices often describe male reactions to women who show up at any place where the male narrator happens to be. Examples include she comes in here, here she comes, she came in looking good, and she came across so cool. This makes sense, given that most country songs are written from the perspective of a male narrator, and that women are therefore described from a masculine viewpoint.

-

Finally, one interesting term that comes up more following “she” vs. “he” is calls. This term is primarily used to describe talking on the telephone (she calls him), or referring to the male narrator using a term of endearment (e.g. she calls me honey / buttercup / baby, etc.)

Men

-

The number one term that is more frequent in country lyrics following “he” vs. “she” is stood. On the one hand, the lyrics sometimes evoke the “strong silent type” who stands in the middle of the action - what’s important is his presence and not necessarily his actions or words (e.g. He stood and he stared a while when their eyes met or He stood there smilin’, holdin’ on). On the other hand, the term is sometimes used to represent the male character’s values or beliefs, as in He stood for Uncle Sam. All in all, the use of the word stood evokes a man who stands steady in his boots, regardless of the situation, and who stands up for his beliefs and values.

-

Interestingly, thought is more common in country lyrics following “he” vs. “she.” Examples include he thought that she’d surely run away, happiness is what he thought he’d find and he thought she’d be sitting home crying. To me, this suggests that the inner life of men is more taken into consideration, which is understandable if most of the country songs are told from the perspective of a male narrator. But the comparison to the patterns for women we saw above is striking; in country music, women want, need, and like, but men think.

-

There are two different words in the chart that refer to seeing - (saw & looked). Men, more so than women, are described as observers in the situations in which they find themselves. For example, he saw the hit, the run, the slide, there ain’t no bigger fan, well he looked me up and he looked me down, and he looked at me with knowing eyes. Seeing and looking are particular types of action that fit in with the larger pattern of male agency in popular country music lyrics.

-

Finally, there are two words that describe men (vs. women) in absolute terms: always and never. Lyrically, it is perhaps easier (arguably too easy) to use these terms to describe a character in a song. Examples of always include he always sang a cowboy’s song, he always drinks for free, he always had a plan, while examples of never include he never said a word, he never had a lot of luck with the ladies, and he never polished his boots. By describing men in these absolute terms, country music lyrics paint male characters with certainty as solid, inflexible, with little room for ambiguity or nuance.

Differences Between How Women and Men Are Described in R&B/Hip-Hop Music

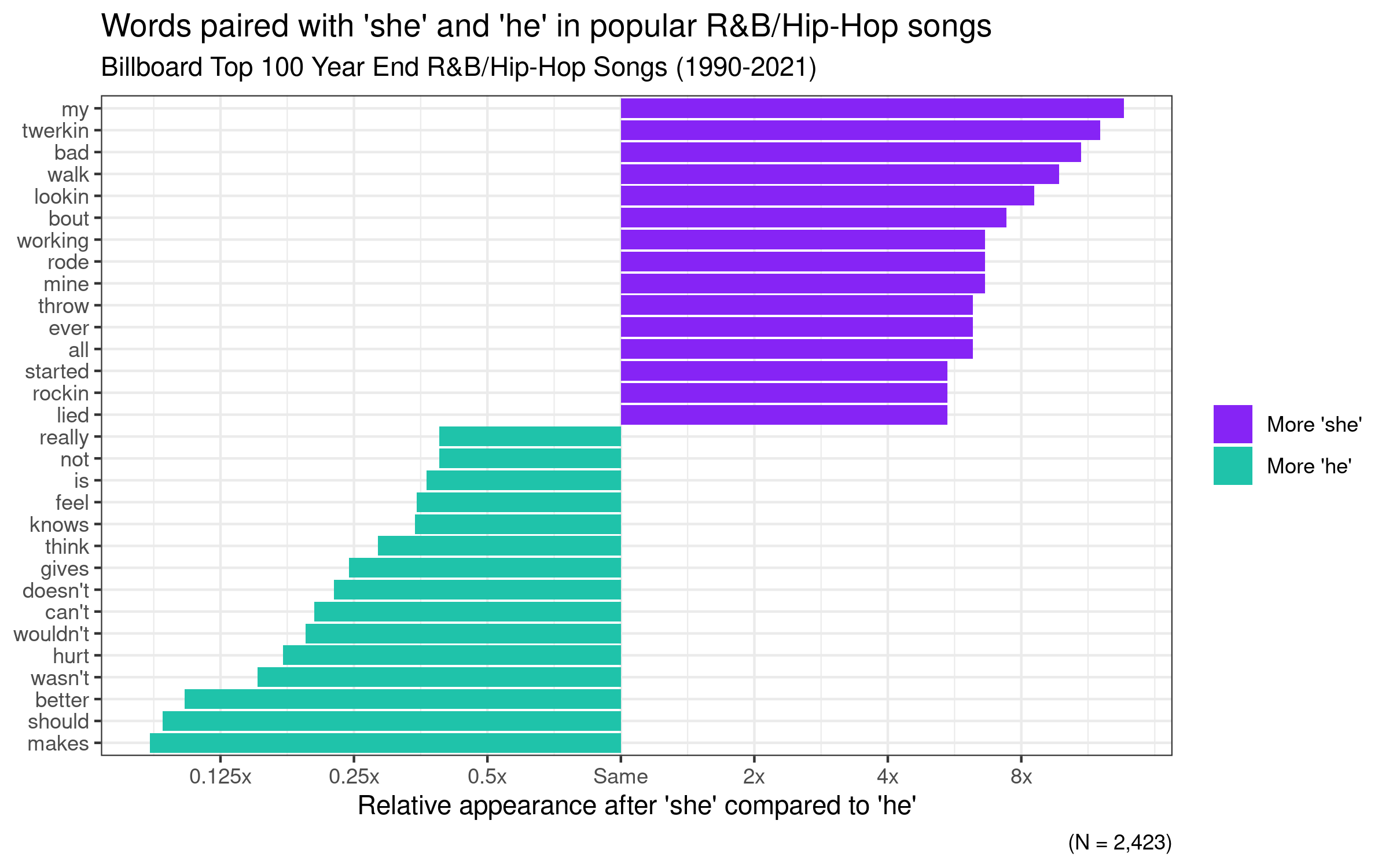

The plot for R&B/hip-hop music looks like this:

It is clear that there are also differences between how men and women are described in R&B/hip-hop music. These are some of the things that I find striking:

Women

-

The number one term that distinguishes women vs. men is my (also note that mine appears in the list). In the R&B/hip-hop song lyrics, there are many different examples of what the woman is in regards to the (mostly male) narrators: she my girlfriend, she my fiance, she my better half, along with she my lil’ boo and even she my therapist. Nearly all of these mentions are meant as compliments, but what they all have in common is that the woman is defined in terms of her relationship to the male lyricist.

-

The second term that distinguishes women vs. men is twerkin. For the uninitiated, twerking is an act “performed chiefly but not exclusively by women, [in which] performers dance to popular music in a sexually provocative manner involving throwing or thrusting their hips back or shaking their buttocks, often in a low squatting stance.”. In a way, it makes sense that twerkin appears more following she than he, as it is a dance move performed mostly by women, and because as we saw in the previous post, a big theme in hip-hop/R&B music is “the club.” Nevertheless, it is an inherently sexual description that portrays women as objects of desire.

-

The third term in R&B/hip-hop lyrics that occurs more frequently following “she” vs. “he” is bad. Some examples include she bad to the bone, she bad as it get, she bad as hell, and she bad as controversy. These lyrics suggest that bad is not necessarily meant in a negative way. It seems to be related to the notion of the bad bitch, who according to Urban Dictionary, is a “badass, solid chick with self respect.” In other words, the R&B/hip-hop lyrics describe women (not men) as bad as a compliment (although using a word that is, in most other cases, used to describe something negative).

-

Finally, there is a cluster of words that are more common after “she” vs. “he” that are related to physical appearance: lookin, working, and rockin. In the lyrics texts, lookin often refers to the woman’s appearance (e.g. she lookin’ decent), working often refers to physical attributes (e.g. she working that back, she working them jeans, etc.), and rockin often refers to physical appearance or clothing (e.g. she rockin that thang, she rockin Sean John [the clothing brand], etc.).

Men

-

Makes is the number one term that is more prevalent following “he” vs. “she”. There are many different uses of “he makes” in the song lyrics (e.g. he makes his money, he makes a mess, he makes love etc.). What they all seem to have in common is action and agency - men, in contrast to women, are doing things in the hip-hop lyrics, imposing their way upon the world.

-

Should is the second term that differs the most between “he” and “she.” The use of should is interesting because it describes the way things ought to be, not the way the they actually are. Examining the R&B/hip-hop lyrics, should is often used when depicting bad or messed-up situations, and suggesting how things might be better if only the male character acted differently (he ain’t gonna love you the way he should, a man would treat a woman like he knew he should, he probably think he could… but I don’t think he should, I’m colder than your man he should be your ex now). This analysis suggests that the R&B/hip-hop lyrics are more likely to take a position on how men (vs. women) ought to act (vs. how they are currently behaving).

-

A final theme that emerges from this analysis is that negations (e.g. wasn’t, wouldn’t, can’t, doesn’t) are more commonly used following “he” than “she” in R&B/hip-hop lyrics. These words describe the way things are not, in contrast to the way things are. Examples include he wasn’t frontin’, he wasn’t man enough, he wouldn’t believe us, he can’t seem to keep hisself out of trouble, for his life he can’t tell the truth, he doesn’t know he’s to blame, and [he] acts like he doesn’t even care. This use of negations describes male (vs. female) song characters in opposition to how they actually are - in terms of what he wasn’t, doesn’t, wouldn’t or can’t do or be.

Summary and Conclusion

In this post, we took R&B/hip-hop and country songs from the Billboard Year End 100 song lists from 1990 through 2021 and used the tidytext analytic framework to examine how both music genres describe women and men. Specifically, we looked at two-word combinations called bigrams and examined the words that were most likely to be paired with “she” and “he”.

The first analyses examined the most common words and found that, in both country and R&B/hip-hop, there were more words that followed “she” as opposed to “he.” In other words, the lyrics for both genres were more likely to contain descriptions of women vs. men. This is likely due to the overwhelming gender imbalance in both genres among the performers represented on the music charts; because men are the singers/rappers in these mainstream genres (where LGBTQ+ themes are not common), and because (as we saw in the previous post) love and romance is a frequent subject in both genres, the lyrics more often focus on descriptions of women. Nevertheless, in both country and R&B/hip-hop lyrics, the top words following he/she were largely the same within each genre. Country lyrics are focused on what women and men are saying (said, says), what they were doing (was, had), and what they are not (don’t, ain’t, can’t) while R&B/hip-hop lyrics are focused on what men and women have (got), say (said), are (was), and what they will do in the future (gon).

We next examined, within each genre, the differences between words that followed “she” vs. “he.” In country music, women (vs. men) were more likely to be described in terms of what they desired, needed or liked (often men or love), as givers (of kisses, love, affection, etc.), as falling in love (of course, with a man), and as calling (either using the telephone or calling a male narrator by a nickname such as honey, buttercup, etc.). In country music, men (vs. women) were more likely to be described as standing in the middle of the action (e.g. the strong silent type) or standing up for their values or beliefs, as thinkers whose inner life is worthy of consideration in the song lyrics, as observers who saw and looked at the world around them, and as solid and inflexible individuals who who always or never engaged in certain behaviors.

In R&B/hip-hop music, women (vs. men) were more likely to be described in terms of their relationship to the male narrator (she my girlfriend, she my lil’ boo), as engaging in sexually provocative danse moves (twerkin), as being full of confidence and self-respect (bad), and in terms of their physical appearance (she lookin’ decent, she working them jeans, she rockin that thang). In R&B/hip-hop music, men (vs. women) were more likely to be described as agentic, doing and making things happen, as not behaving properly (with the lyrics taking a position refering to what characters should be doing), and with many negations (wasn’t, wouldn’t, can’t, doesn’t) which serve to define men in opposition to how they actually are (e.g. he wasn’t man enough).

A Mea Culpa From a Music Fan

In sum, these analyses show that, despite the many cultural and musical differences between the two genres, both country and R&B/hip-hop music engage in stereotypical portrayals of men and women (men as strong, agentic “doers” and women as givers, accessories to the males, and sexualized objects of desire).

I’m of course not the first to point out gender imbalances in country music, or the stereotypical portrayal of women in country music (there’s even an entire country song devoted to this). Furthermore, much ink has been spilled in discussing sexist portrayals of women in hip-hop/R&B music (there’s even a whole wikipedia article devoted to this subject). My observations in this blog post are data-driven but they are hardly original.

Despite the gender imbalances and the problematic ways in which men and women are described, I nevertheless remain a fan of both music genres. If you can ignore the lyrics and focus on the music (which I understand not everyone can or will do), both country and hip-hop/R&B music have many unique and compelling qualities. Hip-hop is a celebration of rhythm and rhyme. In the best R&B/hip-hop music, these elements come together in tight, lyrical, energetic package that I personally find very compelling. Country music can be deceptively simple - a single idea told in 3 versus, a couple of choruses and perhaps a bridge. Harmonically, it’s rarely surprising or adventurous (in comparison to jazz or prog rock, for example). However, there is much to appreciate in the musicianship on the records - the bands are composed of terrific musicians playing real instruments, often live, with impeccable skill, feeling, and musicality. The singers are truly excellent vocalists and the production is top-notch. Despite not agreeing with the stereotypical gender roles espoused by certain lyrics, I am still able to appreciate much about both of these musical genres.

Coming Up Next

In our next post, we will return to this dataset once again and use a different approach - dictionary-based thematic coding - to examine themes that country and R&B/hip-hop music lyrics deal with.

Stay tuned!

-

Note that since the original Billboard data were scraped, the site has undergone a redesign and fewer years of data are currently retrievable than in July 2021. ↩

-

This is the case, for example, for the bigram “she cranks” which appears 24 times, but only in one song - Dustin Lynch’s She Cranks My Tractor. ↩