Showing Some Respect for Data Munging

In this post, I’d like to focus on data munging, e.g. the process of acquiring and arranging data (typically in a tidy manner) prior to data analysis. It’s common knowledge that data scientists spend an enormous amount of time munging data, but data analysis, modeling, and visualization get most of the attention at presentations, on blogs and in the popular imagination. In my current role as a “data scientist,” I spend far more time doing data munging than I do modeling. So let’s show some respect for this process by dedicating a post to it!

The data come from a website on which consumers can rate their perceptions of different products in the consumer beverage category. Consumers select a specific beverage, give it an overall rating, and can indicate their perceptions of the drink (specifically, the presence or absence of different characteristics).

Our end goal, which I will discuss in my next post, is to use the ratings to perform a product segmentation, which will give us insight into how consumers perceive products within the beverage category. In order to reach that goal, we have to distill the information about the different beverages and the information from the consumer reviews into a single matrix that will allow us to derive these answers (with the right type of analysis).

As the past couple of posts focused on data analysis using Python, in this exercise I’ll switch back to R.

The Data

As is often the case, the data we need do not exist in a single tidy dataset. There are two different tables that contain different pieces of information about the beverages and the consumer evaluations.

The Review Data

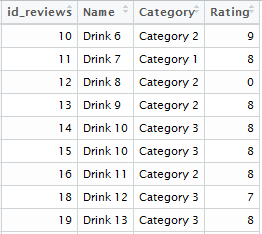

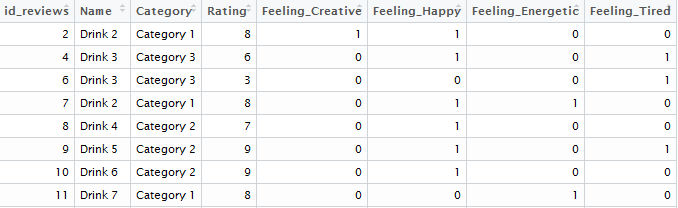

The first dataset contains basic information on the reviews. These data contain one line per consumer review, and have a column describing the review id number, the drink name, the drink category (there are three different categories of beverages in these data), and the overall rating score. Here’s a sample of what the data look like:

The Perceptions Data

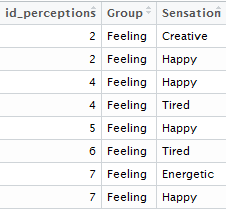

The second dataset contains information on the consumer perceptions. Consumers can indicate their perceptions of each drink on a number of different dimensions. In this post, I’ll focus on the feelings induced by each beverage, characterized by sensations such as “happy” and “energetic.” The dataset contains one line per perception, and has columns indicating the perception “Group” (here we’re focusing on feelings, but other perceptions such as flavor are also present in the data), and the specific *sensation *within the feeling group (e.g. happy, energetic, etc.). This dataset can contain multiple lines per consumer review, if consumers indicated the presence of multiple characteristics for a given beverage. The id number in the perceptions data corresponds to the id number in the review data (though, as is often the case with real-world data, they do not share the same variable name). The head of the second dataset looks like this:

Step 1: Aggregate the Perceptions Data to the Review Level

We first need to aggregate the perceptions data to the review level, in order to merge them in with the review dataset.

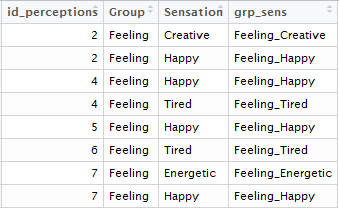

We have a number of different “Groups” of perceptions (e.g. feeling, flavor, etc.), and within each different group, we can have different sensations (e.g. happy, energetic, etc.). We can therefore see the combination of group and sensation to be the sensible unit of aggregation; the combination of both variables provides the best descriptor of the information provided by the consumers.

The perceptions dataset is called “perceptions_reviewid”. We can simply concatenate the group and sensation columns using base R:

# combine group and sensation into one variable called "grp_sens"

perceptions_reviewid$grp_sens <- paste0(perceptions_reviewid$Group, "_",

perceptions_reviewid$Sensation) The head of our dataset now looks like this:

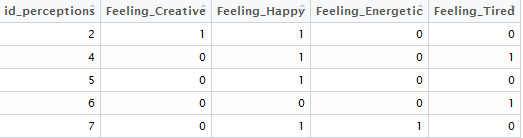

In aggregating this information to the review level, we are faced with two basic issues: 1) transforming the data from the “long” to the “wide” format and 2) representing the information contained in the combination of group and sensation (the “grp_sens” variable) in a numeric format.

The “long” to the “wide” format conversion expresses our desire to aggregate the data to the level of the review, in order to merge it in with our review dataset. We currently have multiple rows per id (a “long” format); we want to end up with a single row per id with the different levels of “grp_sens” (representing the group and sensation information) each contained in one column (a “wide” format).

The representation of the data in numeric format is critical for further aggregation and analysis. Currently, we have the presence or absence of a given perception indicated with text; in our aggregated dataset we would like the presence of a given sensation (one sensation per column) indicated as a 1, and its absence as a 0.

I used the tidyr and dplyr packages, along with this super-helpful StackOverflow response, in order to achieve this.

library(plyr); library(dplyr)

library(tidyr)

# long-to-wide transformation with numeric indicators

# for presence/absence of each group/sensation combination

# at the review level

perceptions_review_level <- perceptions_reviewid %>%

group_by(id_perceptions, grp_sens) %>%

summarize(n = n()) %>% ungroup() %>%

spread(grp_sens, n, fill=0) Essentially, we first group the data by id and grp_sens and count the frequency of each combination (as each person can only choose each combination once, the only value this can take will be 1). We then ungroup the data and spread out the grp_sens variable into the columns, filling each column with the number of observations per review (which, as we note above, will only take the value of 1). We then fill missing values (which occur when a given level of grp_sens did not occur in a review) with 0. Voilà!

Step 2: Merge the Review Data and Aggregated Perceptions Data

Now we need to merge the two review-level datasets. Our review dataset is simply called “reviews” and our wide-format perceptions dataset is called “perceptions_review_level.”

Before merging datasets, I always like to do some basic descriptive statistics on the key variables used in the merge. This type of checking can save lots of trouble down the road in the analysis pipeline, and is one of the “insider” tips and tricks that isn’t mentioned enough when discussing data munging.

We will be merging on the id variable which is present in both datasets (albeit with a different name in each dataset). Let’s see how many id’s overlap with each other, and ensure that there are no duplicate id’s in either dataset. (Duplicate id’s will mess up many merges/joins, causing a dataset to increase dramatically in length, depending on the extent of the duplication).

# number of perceptions id's that correspond to an id in the review data

sum(reviews$id_reviews %in% perceptions_review_level$id_perceptions)

# 105324

# number of review id's that correspond to an id in the perception data

sum(perceptions_review_level$id_perceptions %in% reviews$id_reviews )

# 105324

# are there duplicate ids for the review data?

sum(duplicated(reviews$id_reviews))

# 0

# are there duplicate ids for the perceptions data?

sum(duplicated(perceptions_review_level$id_perceptions))

# 0 We have the same number of matching id’s in both datasets: 105,324, and no duplicate id’s in either dataset, which means that we can proceed with our merge.

We will use dplyr to merge the datasets, specifying the id variables as the “key” in the merge. We’ll use an inner join, because we can only analyze beverages with information from both sources. We will immediately check to see whether our merged dataset has the correct number of rows (105,324, the number of matching id’s in both datasets).

# merge the review and perception data

# inner join because we only want those with values in both datasets

# it does us no good to have information in only one

# (e.g. drink name but no perceptions, perceptions but no drink name)

review_level_omnibus <- dplyr::inner_join(reviews, perceptions_review_level,

by = c("id_reviews" = "id_perceptions"))

# check the dimensions: rows should be equal to

# the number of matching id's above

nrow(review_level_omnibus)

# 105324 As expected, our merged dataset (called “review_level_omnibus”) has 105,324 rows, the same as the number of matching id’s between the two datasets. The head of our merged dataset looks like this:

Step 3: Aggregate the Merged Data to the Beverage Level

We now have 1 row per review, with differing numbers of reviews per beverage. This is simply due to how the data were generated- consumers (website visitors) could leave reviews of whatever beverages they wanted to, and so our sample is inherently unbalanced in this regard. While many techniques are available for investigating consumer preferences with perfectly balanced samples (e.g. where every member of a consumer panel evaluates every beverage on every perceptive dimension), we will have to aggregate our data to the beverage level for our analysis. This will allow us to understand consumer perceptions of the beverage category across all raters, but it ignores potential variation in perceptions between individual consumers.

There are two different aggregations I would like to do on these data. The first concerns the numeric consumer evaluations. For each drink, we will take the average of the rating variable, as well as the average of the 0/1 perception variables. Because the perceptions data are coded with zeroes and ones, when we take the average of these variables, we are simply calculating the percentage of the reviews per beverage that contained a given perception (e.g. the percentage of reviews for a given beverage that indicated “happy” feelings).

# get the mean values per beverage: rating and perceptions

drink_level_perceptions <- review_level_omnibus %>%

group_by(Name) %>% summarise_each_(funs(mean),

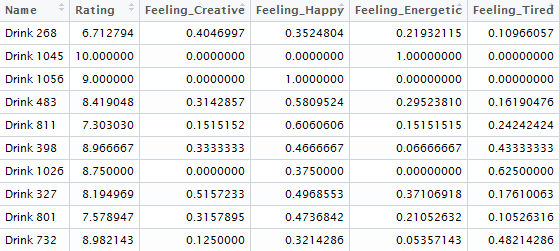

names(review_level_omnibus[,c(4:ncol(review_level_omnibus))]) ) This aggregation yields a dataset whose head looks like this:

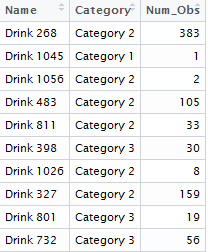

The second aggregation concerns the Category (there are 3 different beverage categories in our data) and the number of reviews for each beverage. Category is constant across each beverage (e.g. each beverage only has one category), while the number of reviews can vary across beverages. We aggregate the data to the beverage level using dplyr:

# get the category and number of reviews per beverage

drink_level_rest <- review_level_omnibus %>%

group_by(Name) %>% summarize(Category = Category[1],

Num_Obs = n()) Which yields a dataset whose head looks like this:

(Note- I didn’t think it was possible to combine these two different aggregations in a single dplyr chain. If I’m wrong, please let me know in the comments!)

Step 4: Merge the Beverage-Level Dataset

We will now merge these two aggregated datasets together on the beverage name (“Name”). (I’ve done the type of checks I describe above on the merging variable, but am not showing them here for the sake of brevity).

# merge drink-level datasets together

drink_level_omnibus <- dplyr::left_join(drink_level_rest,

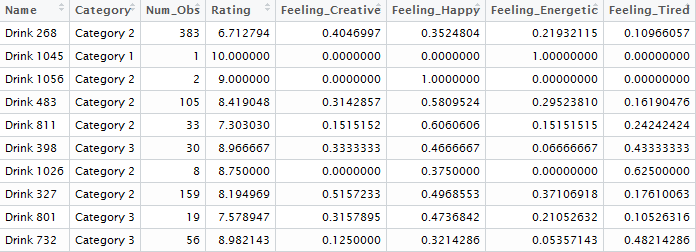

drink_level_perceptions, by = "Name") The head of our final merged beverage-level dataset looks like this:

This is exactly the data format we need to perform our segmentation of the beverage category.

Conclusion: Respect the Munging!

In this post, we took consumer review data about beverages and did an extensive data munging exercise in order to distill the information into a smaller, tidy dataset which we will use for analysis. We first examined the review dataset and the perceptions dataset and understood their structure. We next transformed the perceptions dataset from the long to the wide format, and coded the perceptions with numeric values. We then merged the review and perceptions data together to create a review-level dataset with data from both sources. Finally, we aggregated the review-level dataset to the beverage level, creating a single dataset which contains information on ratings, perceptions, category and number of reviews per beverage. After all of this work, we now have a dataset that we can use to analyze the different beverages!

Data munging and data analysis go hand-in-hand, and we can’t do any analyses without first getting our data in shape. While impressive modeling and visualization will probably always attract more attention, I’m glad I took the time to devote a post to data munging, the less-glamorous-but-equally-important component of any good data analysis.

Coming Up Next

In the next post, I will describe some analyses I have done on the dataset created here, in order to understand consumer perceptions of products within the beverage category. Stay tuned!