Sensographics and Mapping Consumer Perceptions Using PCA and FactoMineR

In the last post, we focused on the preparation of a tidy dataset describing consumer perceptions of beverages. In this post, I’ll describe some analyses I’ve been doing of these data, in order to better understand how consumers perceive the beverage category. This type of analysis is often used in sensographics- companies who produce food products (chocolate, sauces, etc.) conduct research to understand the “product space,” e.g. the way in which consumers understand the organization of a product category according to relevant perceptive dimensions, and the place that different products occupy within that space.

In order to accomplish this goal, we will use PCA (principal components analysis) to analyze the beverage dataset produced in the previous post. Principal components analysis is a technique that tries to reduce a set of variables into a smaller dimensional space. In the current case, we have variables describing a number of consumer perceptive dimensions (e.g. happy, relaxed, etc.). PCA allows us to find a smaller number of independent components that describe the variation in these variables. Within this reduced-dimensional space, we will be able to better understand the relationship among the variables (e.g. the factors that underlie or group the consumer perceptions), and the attributes of the beverages (e.g. where the beverages lie within this lower-dimensional space).

For an excellent introduction to PCA, I highly recommend these wonderfully clear videos from the Hastie and Tibshirani “Introduction to Statistical Learning” online course. François Husson, a developer of the R package we’ll use to do the PCA, has a great open course about sensographics on YouTube (in French only), and some interesting tutorials about PCA in English.1

The Data

[Edit: the data and code used in this blog post are now available on Github.]

For a detailed description of the creation of this dataset, please see the previous post which describes the process in detail. In sum, we have a dataset with 1 row per beverage. For each beverage, we have information on the following consumer perceptions: Creative, Energetic, Joyous, Focused, Happy, Relaxed, Tired and Excited. We also have columns representing the category that each beverage falls into (there are 3 categories of beverages in these data), the drink name, the overall rating score, and the number of consumers who rated each beverage.

For this analysis, I have selected all of the beverages (rows) in the dataset that had more than 100 consumer ratings. This was an analytical choice, made with the goal of only analyzing beverages for which we have a fair amount of consumer evaluations.

The head of the dataset, which is called “feelings,” looks like this:

| Name | Category | Rating | Num_Obs | Creative | Energetic | Joyous | Focused | Happy | Relaxed | Tired | Excited |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drink 268 | Category 2 | 6.71 | 383 | 0.40 | 0.22 | 0.49 | 0.22 | 0.35 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 0.38 |

| Drink 483 | Category 2 | 8.42 | 105 | 0.31 | 0.30 | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.16 | 0.49 |

| Drink 327 | Category 2 | 8.19 | 159 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.50 | 0.29 | 0.50 | 0.30 | 0.18 | 0.50 |

| Drink 79 | Category 3 | 6.24 | 119 | 0.39 | 0.18 | 0.43 | 0.18 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.26 | 0.26 |

| Drink 419 | Category 1 | 8.14 | 173 | 0.45 | 0.34 | 0.54 | 0.24 | 0.57 | 0.31 | 0.12 | 0.55 |

| Drink 698 | Category 2 | 8.33 | 124 | 0.15 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0.44 | 0.33 | 0.73 | 0.09 | 0.34 |

As mentioned in the previous post, the consumer perceptive dimensions here represent the percentage of consumer reviews that flagged a given attribute as present. As an example, 40% of consumers said that Drink 268 (the first row in our dataset) makes them feel “creative.”

PCA

We will use the FactoMineR package to compute the PCA. FactoMineR is a really great package for exploratory data analysis, and it provides a great deal of output that we can use to visualize the results of the PCA.

Before we begin, let’s go over the distinction between two important terms for the PCA implementation in FactoMineR. The first is the variables. These are the measured dimensions that we have information on; in the current example, the perceptive dimensions (e.g. happy, relaxed) are our variables, and they are contained in the columns of our dataframe. The second is the individuals. These are the observations, or the units for which we have measured the information contained in the variables; in the current example, the beverages (e.g. Drink 1, Drink 2, etc.) are the individuals, and they are contained in the rows of our dataframe.

The PCA Code

We first make the beverage names the row names of our dataframe. (This is useful if we want to plot the names of the beverages in the built-in FactoMineR graphs.) We specify that we want to standardize (or scale) our variables; it’s important to do this in PCA because the size of the variation of the variables (directly influenced by their scaling) heavily influences their contribution to the analysis. By standardizing our variables prior to analysis, we ensure that the PCA is not dominated by variables purely because of the size of their variation. We specify that we want 5 principal components (via the ncp command, which stands for “nombre de composantes principales” - the package developers are French 😀). Finally, I indicate the “Category” variable as a supplementary variable. In FactoMineR, supplementary variables are not used in the analysis itself, but rather are used to interpret the results of the analysis. We store the results of our PCA in an object called “PCA_feelings.”

# make the row names of conditions the beverage names

# useful if you want to plot the beverage names

# on the PCA plot

rownames(feelings) <- feelings$Name

# load the FactoMineR package

library(FactoMineR)

# compute the PCA analysis

# we scale the variables and indicate

# the "Category" variable as a "supplementary"

# variable.

PCA_feelings <- PCA(feelings[, c(2, 5:ncol(feelings))],

scale.unit = TRUE, ncp = 5,

quali.sup = 1, graph = FALSE, axes = c(1,2)) The FactoMineR package will produce plots of the variables and the individuals automatically with the option “graph = TRUE,” but I’ve turned that off here. The FactoMineR plots are nice for exploration, but I find them difficult to customize to my tastes, and so below we will produce some graphs using the FactoMineR output, but plotting with the ggplot2 package.

How Many Principal Components to Retain?

Let’s first try to get a sense of the results of the PCA. We started with a number of variables and we are trying to reduce them to a smaller-dimensional space. How can we decide how many principal components are sufficient to explain the variation in our data?

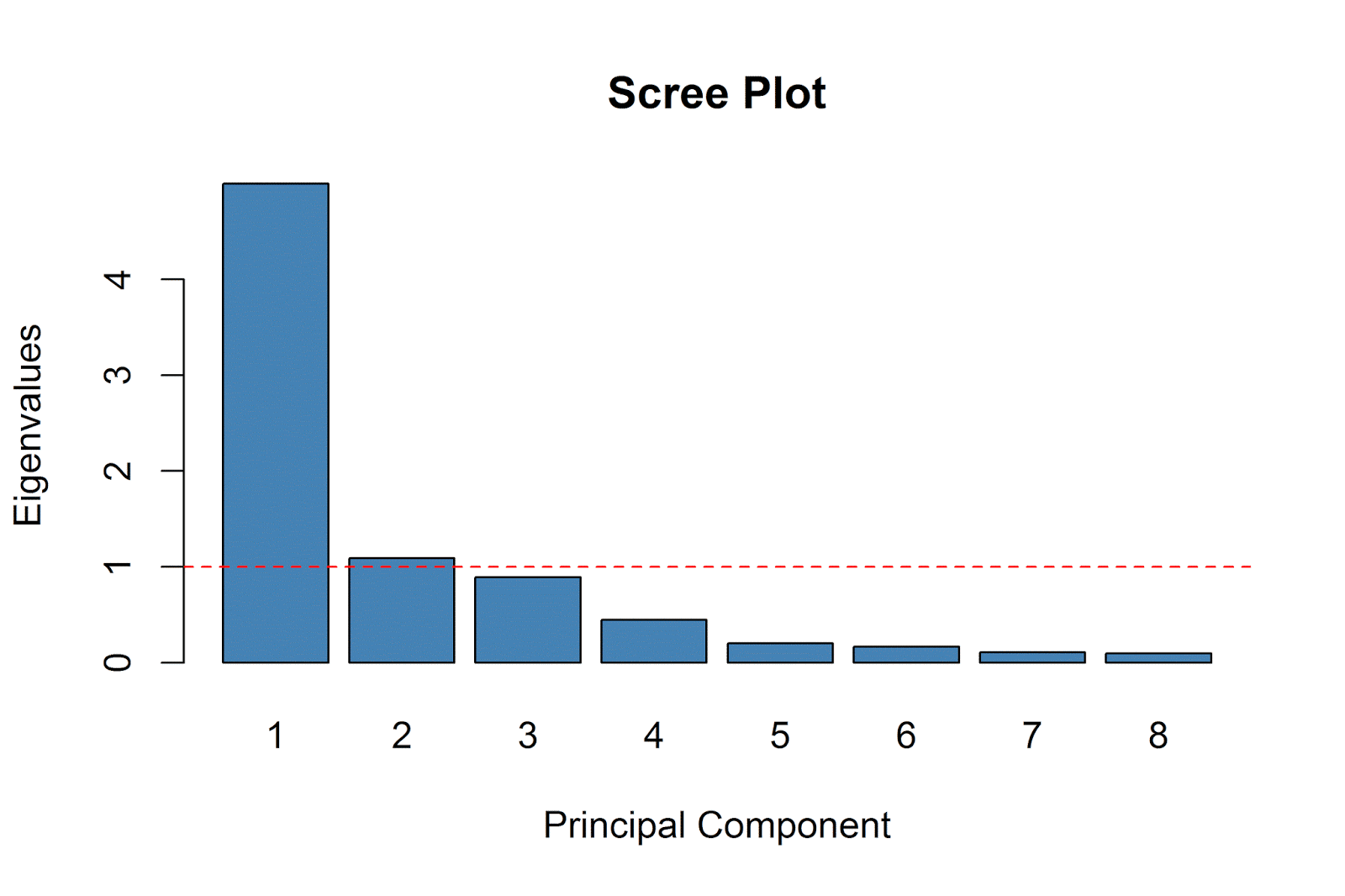

One common way to make this choice is to examine what is called a “scree plot.” A scree plot shows the variation in the data explained by the different principal components. By definition, the first principal component will explain the most variation in the data, and each subsequent component will explain less than the previous one. Based on the scree plot, we can see if there is a “bend” or an “elbow” in the plot; e.g. a point at which the variance explained by the principal components drops sharply. One rule-of-thumb is to only retain principal components which appear before the “bend”- those components are considered sufficient for explaining the variation in the data.

We will plot the eigenvalues (a measure of the amount of variation in the data accounted for by each factor) for each principal component in our scree plot. A principal component with larger (smaller) eigenvalues explains a greater (lesser) amount of variation in the data, and so we are most interested in principal components with larger eigenvalues. Another common rule-of-thumb is to retain the principal components which have eigenvalues greater than 1.

It is relatively straightforward to extract the eigenvalues from the model results object and to plot them using the base R plotting system. I draw a horizontal line on the chart at 1; according to one of the rules-of-thumb mentioned above, we can consider retaining any principal component with eigenvalues above this threshold.

# plot the eigenvalues from the PCA analysis

# using the base plotting system

barplot(PCA_feelings$eig$eigenvalue, names.arg=1:nrow(PCA_feelings$eig),

main = "Scree Plot",

xlab = "Principal Component",

ylab = "Eigenvalue",

col = "steelblue")

abline(h=1,lty=2,col="red") Which yields the following plot:

It is clear that the first principal component explains the lion’s share of the variation in our data. Based on the “bend” or “elbow” rule-of-thumb, we would only retain the first principal component. However, based on the “eigenvalues-greater-than-one” rule-of-thumb, we would consider also retaining the second principal component.

As we are interested in plotting the results of the PCA in a two-dimensional space (called a bi-plot), we will consider the first two principal components as we proceed further with our analysis.

Bi-Plot 1: Examining the Variables (Perceptive Dimensions)

We will first produce a bi-plot of the variables (e.g. the perceptive dimensions). This plot shows the variables in the two-dimensional space defined by the first two principal components.

Note that the code below is somewhat involved, and if you’re just looking for a basic plot, you need go no further than those produced by the FactoMineR package by default. I’m hugely indebted to this wonderful StackOverflow response for describing very clearly how to create such plots using ggplot2. In essence, we first create a dataframe with the coordinates of the variables, extracted from the PCA results object. We then set up the plot of these data using a number of different ggplot2 options.

# bi-plot for variables using ggplot2

# adapted from:

# http://stackoverflow.com/questions/10252639/pca-factominer-plot-data

# first, create the dataset for the variables

vPC1 <- PCA_feelings$var$coord[,1]

vPC2 <- PCA_feelings$var$coord[,2]

vlabs <- rownames(PCA_feelings$var$coord)

vPCs <- data.frame(cbind(vPC1, vPC2))

rownames(vPCs) <- vlabs

colnames(vPCs) <- c('PC1', 'PC2')

# now make the bi-plot

library(ggplot2)

# set up theme for plot

pv <- ggplot() + theme(aspect.ratio=1) + theme_bw(base_size = 20)

# put a faint circle there, as is customary

angle <- seq(-pi, pi, length = 50)

df <- data.frame(x = sin(angle), y = cos(angle))

pv <- pv + geom_path(aes(x, y), data = df, colour="grey70")

# add on arrows and variable labels

pv <- pv + geom_text(data = vPCs, aes_string(x = vPC1, y = vPC2),

label=rownames(vPCs), cex= 2) + xlab('PC1 (62.49%)') +

ylab('PC2 (13.61%)')

# define end points for arrows

pv <- pv + geom_segment(data=vPCs, aes_string(x = 0, y = 0, xend = vPC1*0.9,

yend = vPC2*0.9), arrow = arrow(length = unit(1/2, 'picas')),

color = "grey30")

# specify format for the axis titles and text

pv <- pv + theme(axis.title.y = element_text(size = rel(.65), angle = 90))

pv <- pv + theme(axis.title.x = element_text(size = rel(.65), angle = 00))

pv <- pv + theme(axis.text.y = element_text(angle = 90, size=13))

pv <- pv + theme(axis.text.x = element_text(angle = 00, size=13))

# show plot

pv Which yields the following plot:

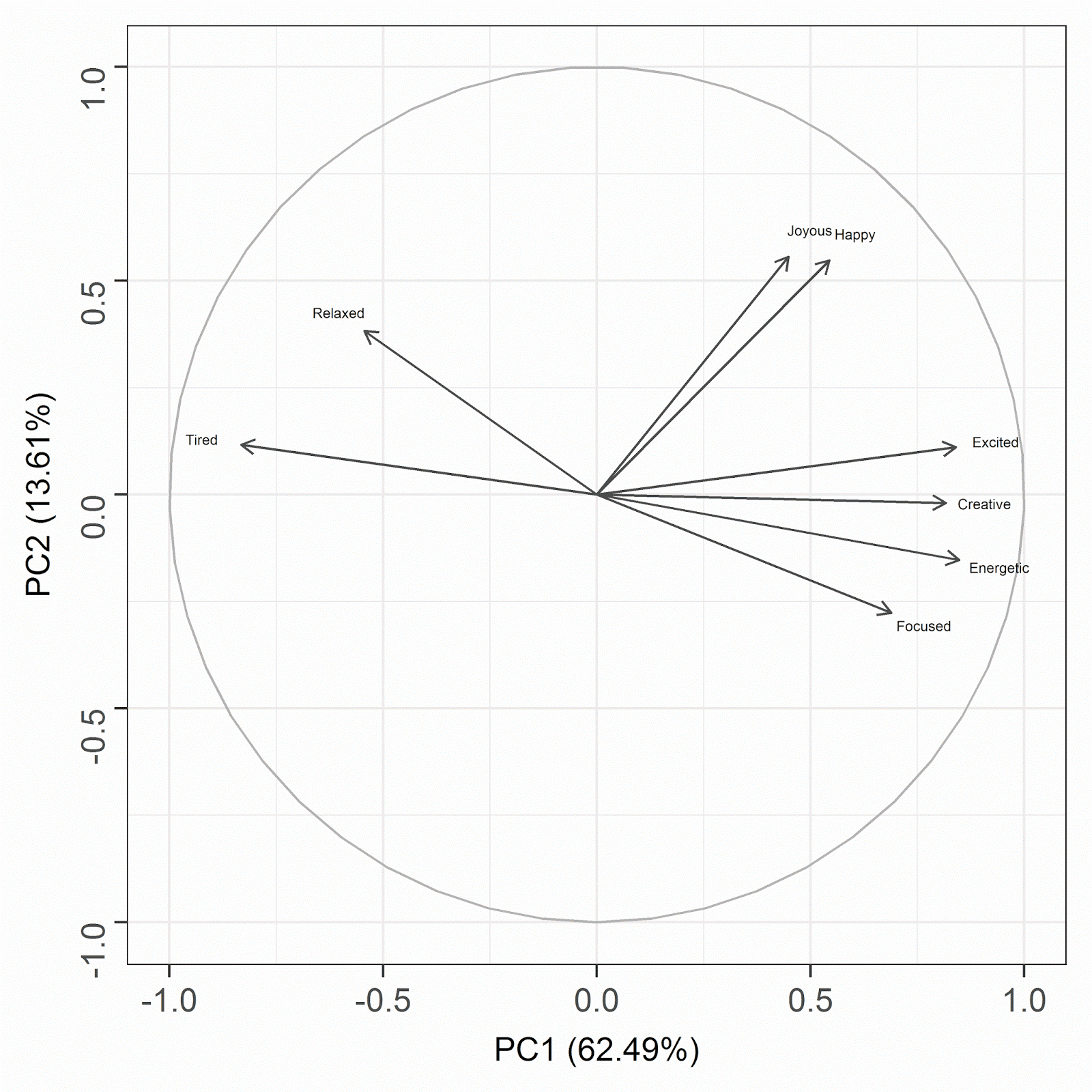

The biplot shows the variables and their inter-relations in the space represented by the first two principal components. The closeness of the arrows representing the variables gives us an indication of their correlation. In other words, variables with arrows that are closer together are more highly correlated. The bi-plot therefore indicates that our 8 perceptive dimensions cluster into 3 groups: relaxed feelings (tired and relaxed), positive emotions (joyous and happy) and excited feelings (excited, creative, energetic and focused).

The bi-plot also shows how the variables are situated in relation to the first and second principal components, which define the x and y axes, respectively. We can see that the first principal component is very clearly defined by two poles of variables, represented on the left by tired and relaxed, and on the right by excited, creative, energetic and (to a lesser extent) focused. This first principal component dominates the analysis (as we saw in the scree plot) and it explains 62.49% of the variance in the perception data. In other words, if we want to understand the primary dimension on which the beverages differ, it would be the dimension of the first principal component, contrasting tired and relaxed feelings vs. energetic feelings.

In contrast, the second principal component explains a much smaller percentage of the variance in the data (13.61%). This dimension seems to indicate positive emotion, and is defined by joyous and happy, and to a lesser extent relaxed.

The dimdesc function in the FactoMineR package computes the correlations between the variables and the principal components; variables that have large positive or negative correlations best define the PC’s.

# display the correlations between

# the variables and the principal components

dimdesc(PCA_feelings) Which yields the following table for the first principal component:

| Variable | Correlation | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Energetic | 0.94 | 4.10E-96 |

| Excited | 0.93 | 1.90E-90 |

| Creative | 0.91 | 1.10E-76 |

| Focused | 0.77 | 6.23E-40 |

| Happy | 0.60 | 2.11E-21 |

| Joyous | 0.50 | 5.12E-14 |

| Relaxed | -0.60 | 2.08E-21 |

| Tired | -0.92 | 3.75E-85 |

And this table for the second principal component:

| Variable | Correlation | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Joyous | 0.62 | 1.45E-22 |

| Happy | 0.61 | 8.87E-22 |

| Relaxed | 0.43 | 3.14E-10 |

| Energetic | -0.17 | 1.57E-02 |

| Focused | -0.31 | 9.29E-06 |

Bi-Plot 2: Examining the Individuals (Beverages) and the Qualitative Supplementary Variable

Next, we will plot the individuals (the beverages), on their coordinates in the two-dimensional space defined by the first two principal components. We will color each beverage according to its Category (1, 2, or 3). We will also plot the qualitative supplementary variable of category in this space.

The code is again somewhat involved, and if you’re not interested in customizing your plots, you can simply use the default plots provided by the FactoMineR package. We use the same approach as for the first bi-plot: creating dataframes with the coordinates from the PCA results object (for the beverages and for the quali supp variable of category), and then specifying the parameters for the plot with ggplot2.

The code to produce the data and the plot look like this:

# create the dataset for the individuals (beverages)

PC1 <- PCA_feelings$ind$coord[,1]

PC2 <- PCA_feelings$ind$coord[,2]

Category <- as.character(feelings$Category)

labs <- rownames(PCA_feelings$ind$coord)

PCs <- data.frame(cbind(PC1,PC2,Category))

rownames(PCs) <- labs

# create the dataset for qualitative supplementary variables

cPC1 <- PCA_feelings$quali.sup$coor[,1]

cPC2 <- PCA_feelings$quali.sup$coor[,2]

clabs <- rownames(PCA_feelings$quali.sup$coor)

cPCs <- data.frame(cbind(cPC1,cPC2,clabs))

rownames(cPCs) <- clabs

colnames(cPCs) <- c('PC1', 'PC2', 'Category')

# plot the individuals (beverages)

# and quali supp variable

# define the plot basics - individuals

g <- ggplot(PCs, aes_string(x = PC1, y = PC2, color = "Category")) + geom_point()

# define the colors, axis limits & labels

g <- g + scale_color_manual(values=c("#8e7600", "#8245cc", "#018d69")) +

xlab('PC1 (62.49%)') + ylab('PC2 (13.61%)') +

coord_cartesian(xlim = c(-5.5, 5), ylim = c(-5, 2.5))

# add the quali supplemental variables

g <- g + geom_point(data = cPCs, aes(x=cPC1,y=cPC2), size = 8)

# show the plot

g Which yields the following plot:

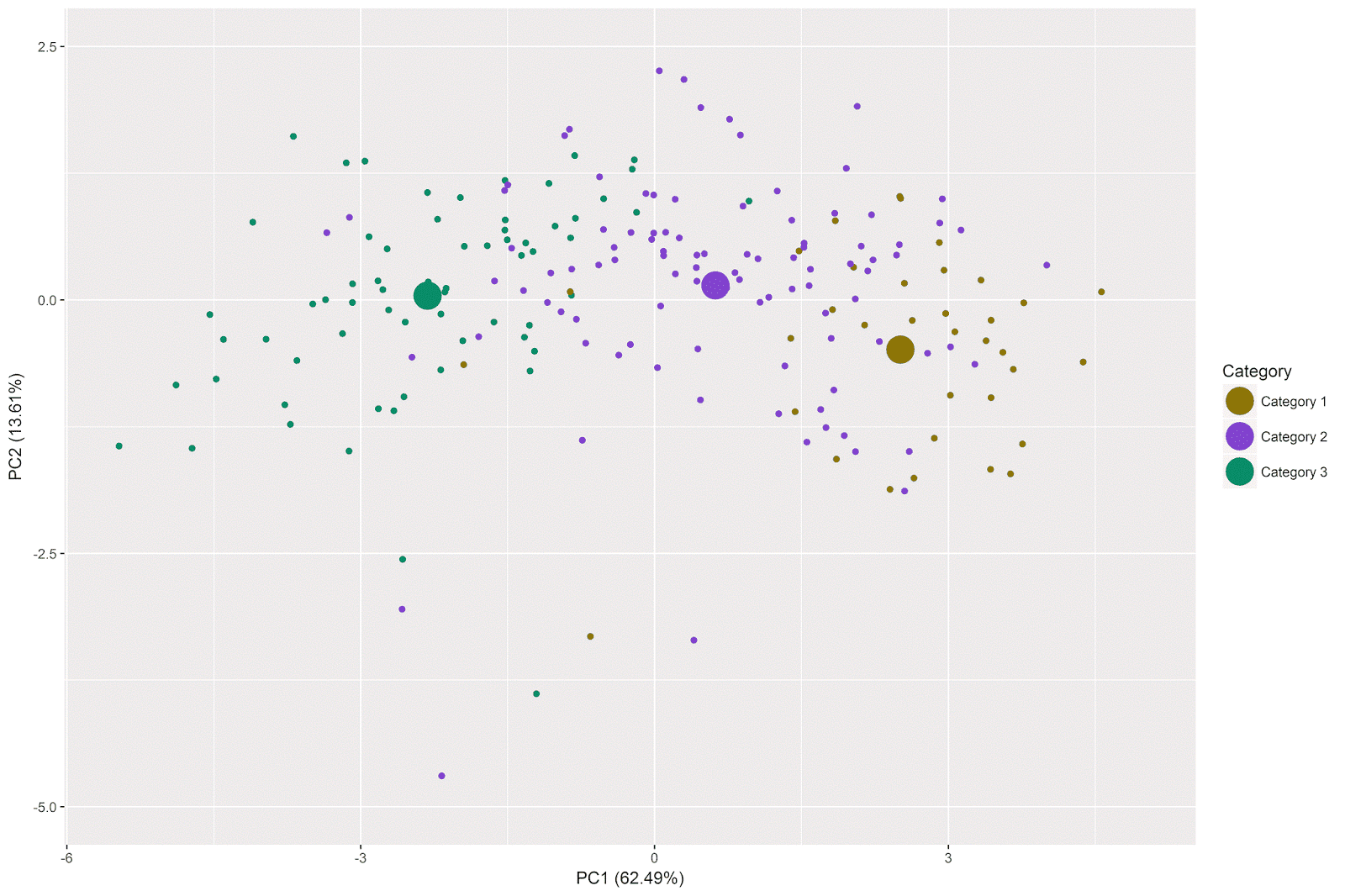

We have colored the points in the plot according to category. The small points represent the individual beverages, and the large points represent the “quali supp” variable, showing the centers for each category in the two-dimensional space defined by the first two principal components.

As is clear from examination of the points for the individual beverages and from the position of the qualitative supplementary variable, there is a definite ordering of the categories of beverages across the the first principal component (displayed on the x-axis). Beverages of Category 1 are higher on this component, indicating that they are more likely to provoke feelings of energy and excitement (think along the lines of energy drinks or coffee, for example). Beverages of Category 3 are lower on this component, indicating that they are more likely to provoke feelings of tiredness and relaxation (think along the lines of herbal teas, for example). Beverages of Category 2 in general fall in the middle, though note that there is some overlap in the ordering of the beverages of the different categories across the first principal component.

There is far less variation among the categories on the second principal component (displayed on the y-axis). The center for Category 1 is below zero, while those for Categories 2 and 3 are slightly above zero. However, the differences among the categories on the second principal component are far smaller than their differences on the first principal component. Note that while individual beverages from the various categories vary along the second principal component, the overall averages per category do not differ dramatically along this dimension.

Bringing It All Home: Mapping Consumer Perceptions of the Beverage Category

What have we learned from this exercise about how consumers perceive the beverage category?

First, the PCA analysis helped us to distill the information regarding our many variables (perceptive dimensions) into a smaller-dimensional space defined by two principal components. An examination of the variables bi-plot showed that some of the perceptive dimensions were highly correlated with one another. Specifically, we can spot 3 clusters of variables, corresponding to relaxed feelings (tired and relaxed), positive emotions (joyous and happy) and feelings of excitement (excited, creative, energetic and focused).

Second, our analysis of the principal components themselves revealed that the first PC explained most of the variation of the data. This principal component was defined by two opposing poles: on the one hand by feelings of energy, excitement and creativity, and on the other by feelings of tiredness and relaxation. Therefore, if we were to summarize how consumers perceive the beverage category in terms of our perceptive dimensions, we could simply say that consumers differentiate beverages according to how activated or energetic they make them feel, versus how tired and relaxed they make them feel.

Finally, an examination of the individuals (beverages) revealed a clear distinction among the categories of beverages according to the first principal component. Beverages from Category 1 were located on the “excitement” pole of the first principal component, indicating that they are much more likely to provoke energetic feelings. Beverages from Category 3 were located on the “tired/relaxation” pole of the first principal component, indicating that they are much more likely to provoke feelings of fatigue and calm.

Therefore, not only do we understand the basic underlying components of our perceptive dimensions, but we are also able to place our products and our product categories in the space defined by these dimensions. Such insight can help guide, for example, a marketing strategy wherein beverages from Category 1 are marketed as giving an energetic boost, promoting consumption of the drinks in the morning and afternoon, while beverages from Category 3 are marketed as helping one unwind at the end of the day.

Conclusion

In sum, in this post we used PCA to understand how consumers perceive products in the beverage category. Our PCA allowed us to distill the information contained in our variables (consumer perceptive dimensions) into a smaller-dimensional space, providing insight into the structure of the product category and allowing us to place our beverages and beverage categories within this space. With this information, we can better understand the product and the product category, and use the information to help guide our business (for example, in communicating the benefits of our beverages to the public).

Coming Up Next

In my next post, I will use a type of deep learning, word2vec, to make a vector space model with the text of wine descriptions. We will use this approach to understand word similarity in the wine texts. Stay tuned!

-

I will mention that I met Professor Husson at the useR! conference in Brussels in June. He was very nice when I tried to explain a bit about this project to him in French. ↩